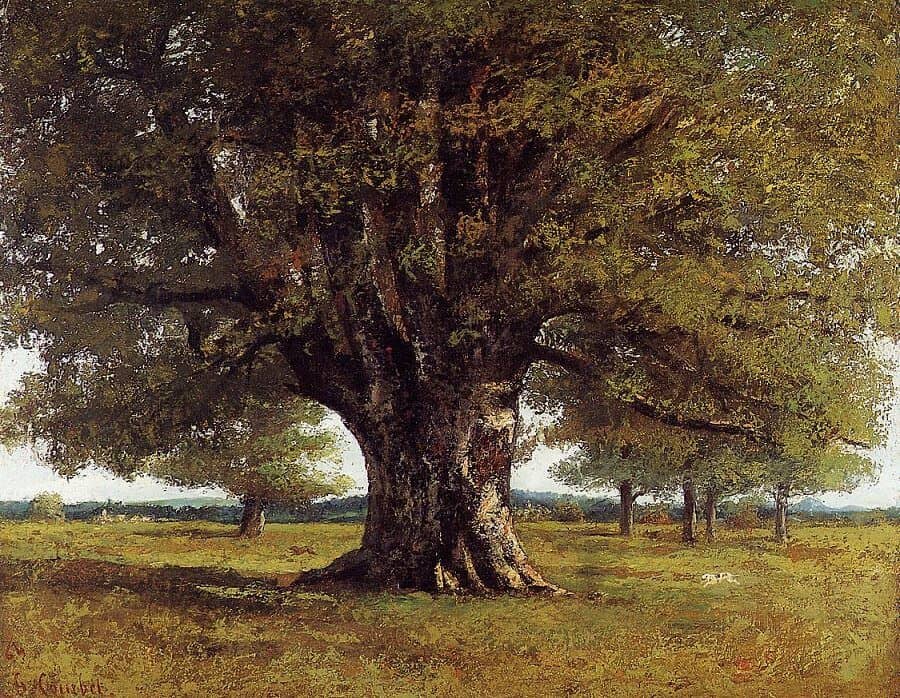

The Oak of Flagey, 1864 by Gustave Courbet

In this painting of the giant oak near his father's native village of Flagey near Ornans, Courbet makes use of every device to convey the sense of the strength and massiveness of the great tree. Rooted in the absolute center of the canvas, the thick gnarled trunk moves up and out into a maze of leafy branches, whose thick foliage covers the upper two-thirds of the pictorial field with a mass of active brushstrokes that are cut off by three sides of the canvas. The ancient, still growing tree pushes way beyond the borders of the painting. Thick, dark, brooding, and powerful, this is visibly not an Impressionist tree: its meaning does not lie in dappled light or in the civilized pleasures one might enjoy beneath it. The painting has been interpreted as a self-portrait, and this is not unreasonable, given the significance of the tree and Courbet's capacity for psychic identification with the objects that he painted.

The oak tree had an intrinsic symbolism of long duration in transalpine European culture: it is the tree of the Druids, of the ancient pre-Roman past. The reference to Vercingetorix in the title brings this symbolism to a specific focus on the culture of the Gauls, whose leader he was. The idea of the Gauls as being the true ancestors of the French people emerged during the course of the 1789 Revolution. They were constructed as the Ur-population, le vrai peuple repressed by Romans and later by the Frankish founders of feudal aristocracy, finally in the modern world rising to throw off the yoke of servitude. Vercingetorix became a popular hero, the brave warrior who fought Caesar's great armies and was finally defeated in A.D. 52 at the battle of Alesia. Around the time this painting was made, there was a controversy, archaeological with strong political overtones, in which the location of the site of the ancient battle was disputed. One possible site was in the neighboring Cote d'Or; the other was near the village of Alaise, close by Flagey, where Courbet's father was born. Courbet's subtitle mentions not only Vercingetorix but "Caesar's camp near Alesia, Franche-Comte." Local feeling ran high in favor of the Franche-Comte site, the more so as Napoleon III, author of a study of Julius Caesar, was in favor of the Cote d'Or location. The latter won, but The Oak of Vercingetorix remains. It is characteristic of Courbet that he entered this controversy, and that he did so not by falling into the literalism of illustrating the historical past but by portraying a great and ancient tree.