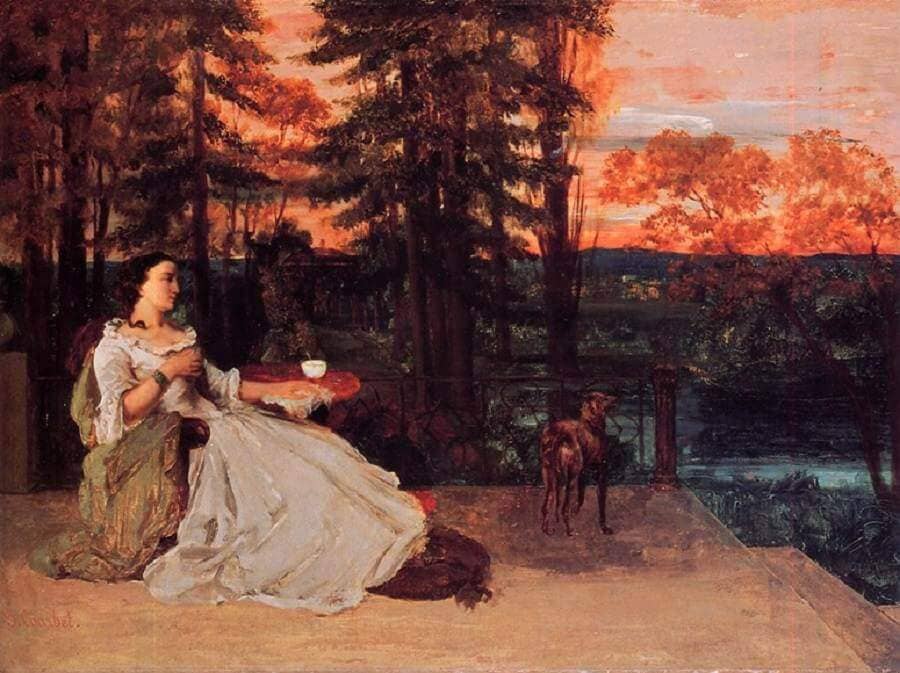

The Lady of Frankfurt, 1858 by Gustave Courbet

Courbet came to Frankfurt in the fall of 1858, after a year in which almost nothing is known of his whereabouts. He had gone to Brussels, where his paintings were being shown, in the previous autumn and stayed for some unspecified period, reportedly spending much of his time enjoying the pleasures of the taverns. It was a strange and unproductive year, and one can only speculate that it may have represented a crisis of confidence brought on by the awareness that some of his Utopian dreams were not capable of realization. Bruyas's patronage - neither so euphoric nor active as in the beginning - would in any case not ever enable him to bypass the reactionary officials and hostile juries of the Salon system. In this context, the eagerness of artists' groups in Brussels to show his work prompted a strong response, and he was there again - or perhaps still - in the summer of 1858. Courbet was equally pleased by his reception in Frankfurt, where he was given a studio in which to work on large canvases. In addition, he had the good fortune to be introduced through his friend the photographer Carjat into the family of the banker Emil Erlanger. Through these social connections he was also able to take part in the grand stag hunts of the Black Forest, which proved to be an energizing source of ideas and motifs. Yet despite all this, he wrote to his family in December of 1858 that he had not written to them because

I could only write insignificant things, full of unhappiness, nothing very interesting. I ramble through foreign countries to find the independence of mind that I need and to let pass this government that does not hold me in honor, as you know.

In The Lady of Frankfurt this strain of melancholy in the midst of pleasant surroundings makes itself felt. The subject is apparently simple: a lady, finely but not formally dressed, is taking a comfortable cup of tea on her terrace, overlooking a spacious park. The model is undoubtedly either Madame Erlanger or one of her friends, but the painting is not conceived as a portrait. Its somewhat mysterious mood emerges in part from the sense of inwardness and self-absorption of the figure, who appears to be waiting for someone or something. This waiting becomes apprehension in the tense figure of the elegant dog. The impression given of capturing a magical, evanescent moment is also caused by the openness and transparency of the paint handling in this not fully finished work, and by the fact that the artist's changes in composition have become apparent to the viewer. The male figure originally seated at the little table was painted over with a tempietto in the park, but now looms ghostlike next to his companion, who in any case is gazing far beyond him. The terrace, once extended to the edge of the canvas, now ends in steep steps which provide a view out over a body of water. The light of the evening sky sifts through a mix of dark fir and autumnal foliage, scribbled in with the kind of spontaneous, feathery touch of which Courbet was the master.