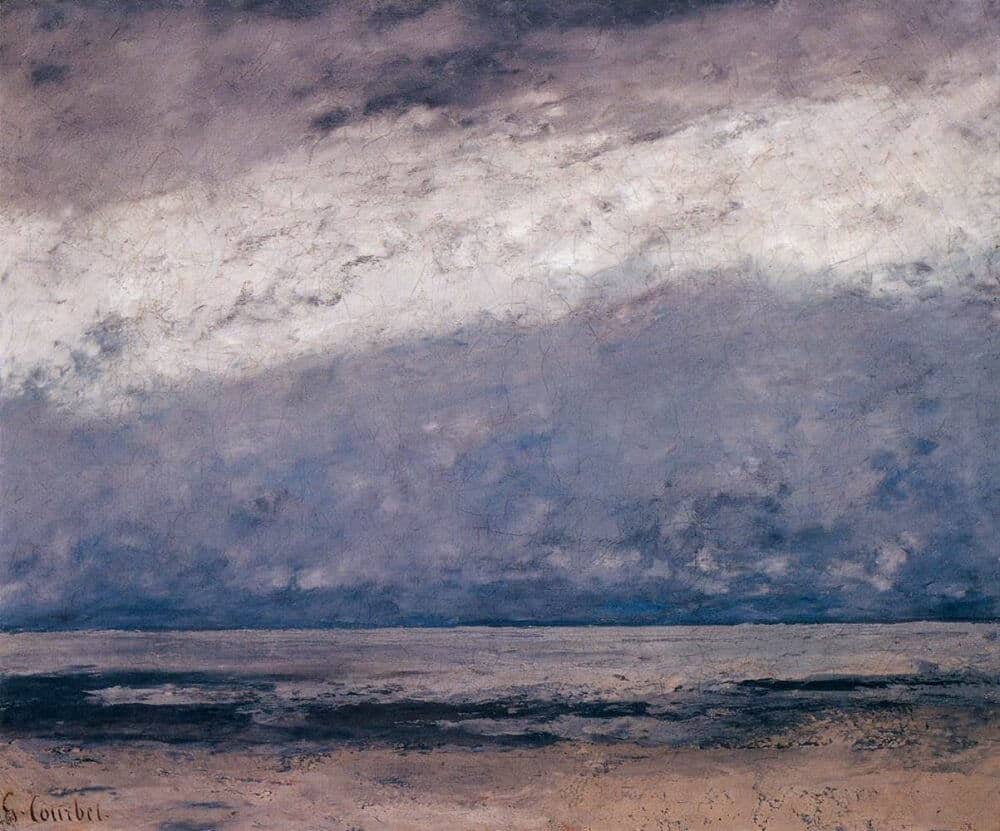

Marine, 1865 by Gustave Courbet

Courbet was delighted with the society at Trouville, and at neighboring Deauville, where in 1866 he stayed with the Count de Choiseul. But although some members of the resort population are represented in his commissioned portraits, the summer public as a whole did not find its way into his paintings of the sea and shore. Almost without exception his seascapes are unpopulated, except by an occasional boat abandoned on the sand or sailing far away on the horizon.

When he looked, as a relative newcomer to the painting of seascape, to the work of Boudin, he paid attention to the low horizons and the wide high skies rather than to the sociably grouped little figures along the shore. He was moved by the vast expanses of sea and sky and by the shifting, subtle luminosity of the Channel coast. This experience is at its most intense on this particular stretch of coast when the tide is low. The beach is very flat for a long way out, so that at low tide there is an expanse of wet, light-reflecting sand that merges into the line of the sea, and at certain times a wide stretch of very shallow water. The relations of color and tone between the three elements of earth, sea, and sky are close and constantly shifting. Courbet focused on this experience and made it the subject of one whole group of his Trouville seascapes, the Low Tides. In response to the experience he lightened his palette and worked directly with lighter pigments, rather than building up to light from dark, which had been his lifelong method.

The painting shown here is one of the most brilliant of the series. The richly varied, dragged color defines the damp sand with its tidal pools, the mid-distant expanse of dark green shallow water moving to deep blue at the horizon, and the wide sky in which heavy white clouds filter the rays of a late sun. At the same time the tonal and coloristic play of the pigments create a structure of pure luminosity on the surface of the canvas. For the viewer, these two experiences of depth and surface are inextricable from one another. The result is an excellent example of how a painted surface that can be seen purely coloristically and tonally all on one plane can also convey, paradoxically, a vast depth of space. These Low Tide canvases are thus remarkably akin to later Impressionist painting, in particular that of Monet at Giverny, in that they convey an immediate visual response to a specific place and at the same time construct a web of paint that can be experienced for its own sake.